On the turntable: "Kindred Spirits: A Tribute To The Songs Of Johnny Cash"

Wednesday, December 31, 2014

Sunday, December 28, 2014

Sunday Papers: Murasaki Shikibu

"How vast must the mountains of love be, that all those who enter them still lose their way."

--Tale of Genji, Royall Tyler trans.

On the turntable: "Celtic Christmas"

On the nighttable: Jonathan Lethem, Chronic City"

Monday, December 15, 2014

Slice of Life

In a hotel, watching a prep cook chopping lettuce without looking at the knife. Samurai!

On the turntable: "Flamenco: Fire and Grace"

Wednesday, November 26, 2014

Illusion

I'd been at sea for the past thirty-six hours, aboard a ship whose logo was a pair of seahorses that looked like they might be butting heads. There wasn't much to do on sea days of course, so the friendly crew had created an itinerary that was almost too full. The motto seemed to be: "Relax. All you need to do is enjoy." And enjoy I did, sitting in a deck chair for hours, alternating between reading a book, or staring out at all that water passing beneath. There were the odd distractions, like the dolphins playing in the ship's wake, or the dark evening when a channel pilot had stepped out of a doorway many stories below onto a smaller vessel running parallel, which then turned and sped toward the lights of Key West shimmering beyond the grey. But most of the time the sea looked just as it does on film, capable perhaps of showing only three expressions: grinning brightly under perfect blue skies; cool and garlanded with puffy clouds; or the gritted teeth of whitecaps on a stormy night.

After a long time at sea, there is some relief to be found in a return to dry land. One of first things I saw when boarding the bus was the squat church of San Francisco de Asissi, looking weathered and tired against the flash and noise of Cozumel. The bus door vacuumed shut, but not before I'd gotten a whiff of that tell-tale smell familiar to those countries once known as 'third world,' of food both rotting and cooked, with just a hint of diesel fuel underneath.

The bus took us past sleepy Mexican scenes of men in straw hats sitting in the entrances of small shops (one of which was named Lolita Lolita), dogs sleeping in the shade of police cars, and laundry hanging in front of concrete homes, all shaded by palm and bougainvillea. There were also the odd political posters, most often showing a dapper mustachioed man named Zapata.

On the bus, our guide was talking things Mayan in an exuberant voice, punctuated often with abrupt "How's?" and "Why's?" as if in Spanish. He mentioned that the Mayans use a 52-year calendar, at the end of which the people tend to destroy a great many of their possessions. This may account for the shards of broken concrete strewn simply everywhere.

The bus stopped briefly at a small souvenir shop, and I got off to stretch my legs. There's something about Mexico that makes you walk slowly. Maybe it's the heat, or the earthen look of the tiles, or the squat people built closer to the ground.

Back on board. The jungle on both sides of the road were alive in a way that deciduous forests aren't, the mangroves, cashew, mango and sugarcane all literally pulsing with movement. It was far different than the mellow stillness of wood. Pressing in, ever pressing in, as if ready to caress the bus whose tinted windows frustratingly muted the brilliance of the blues and greens outside.

But we got these, and the heat, full force at the ruins proper. A fleet of bicycle taxis whisked us along dusty trails that were punctuated with the mammoth edifices of grey stone. I climbed to the top of one pyramid, looking out over the green that stretched away endlessly in all directions, much like my recent companion the sea. I imagined other ruins out there, just waiting to be found. I had read that these temples and ball courts had been built for the priests and higher classes. The poorer peasants lived in smaller huts out in the jungle. Things had changed very little in the subsequent 1200 years. Earlier on, all along the highway leading inland from the beaches, were the large gated courtyards surrounded by similar dull pillars of stone, which framed the palaces which as holiday homes for the moneyed north. Their darker, flat-faced servants still lived in the same simple squalor of their ancestors, a squalor though which my tall bus rode proudly past.

On the turntable: "The Rough Guide to Morocco"

Wednesday, November 19, 2014

Down there

He is buried in grave down there somewhere, in a grave with my name on it.

My plane had left La Guardia just under an hour before. From the window, my eyes traced the broad Navesink River to the town in which I had grown up, and in which my father had died. I wondered: do thoughts and emotions remain in the place in which they sprang to life? If so, there is a patch of lawn fertilized by the sadness and fears of a young boy trying to make sense of the confusing dissolution of his parents' marriage.

Forty years and 30,000 feet removed, the boy was now in the midst of his own divorce. Not as messy, but he was trying just the same to protect a similarly uncomprehending child from becoming collateral damage. The boy is now a man of an age slightly younger than his father had been when his heart had finally lost the rebellion against the anger and hatred that had ever defined him.

On the turntable: "Texas-Czech Bohemian - Moravian Bands"

Saturday, November 15, 2014

Sleeping in the City that Never Sleeps

"Sorry buddy we're closed."

In my near three years away, I'd forgotten about the unique, "we're all pals here" chummery of the American vernacular. The only customers within were a pair of stern-faced businessmen taking shelter in this darkened bar that smelled of ridiculously strong drinks. Based on their expressions, it seemed to be as necessary as medicine.

My former yoga teacher used to call our American society adrenally charged. This applies too to our choice of depressants. And here I was seeking out my own, a body clock set to Tokyo having wound up my mind. But the bed I had been lying in for the past two hours was in midtown Manhattan. I had been riding that push me-pull you feeling of insomnia, that tension between do I get up vs. I'm think I'm starting to drift. The former won out, and as I made my way out I glanced at the clock. 11:03 pm.

There was a lounge on the 4th floor that had comfy sofas and internet. But upon arrival I found that they'd stopped serving beer at the top of the hour. The bar on the first floor was similarly closed. As was the cafe across the street. So too were the bars in the four hotels on this or the adjoining blocks. In the last, I had found a sympathetic staff who told me that they'd like to serve me but had already dropped the register till down the safe. I asked them, "What the hell has happened to this city."

I went over to visit Duane Reade. They had a good selection of bottled craft beers, but were only sold as six packs. The only singles available were the usual bilgewater of the American mainstream brands.

I returned thus to my bed, my frustration a stimulant, which did little to help with the drift.

On the turntable: "Friends of Old Time Music"

Friday, November 14, 2014

(Untitled)

The mountain stands

Unblinking,

As seasons come and go.

Unblinking,

As seasons come and go.

On the turntable: Keith John Adams, "Daytrotter Session"

Wednesday, November 12, 2014

(Untitled)

French impressions come home.

Van Gogh's 'Starry Night,'

In ginkgo roots.

Van Gogh's 'Starry Night,'

In ginkgo roots.

On the turntable: "Acoustic"

Monday, November 10, 2014

(Untitled)

Autumn rains

Shed their tears for

The year's last green.

On the turntable: Bryan Scary, "Daytrotter Session"

Saturday, November 08, 2014

Thursday, November 06, 2014

(Untitled)

Wizened old gent

Enjoys from his front row seat,

The race of time.

Enjoys from his front row seat,

The race of time.

On the turntable: Paleo, "Daytrotter Session"

Tuesday, November 04, 2014

(Untitled)

The source of life of the source of life.

Beneath the eternal shimmer,

Things begin to stir.

Beneath the eternal shimmer,

Things begin to stir.

On the turntable: Rock Plaza Central, "Daytrotter Session"

Sunday, November 02, 2014

Sunday Papers: Frederic Gros

"To arrive on foot at a place whose name one has dreamed all day, whose picture has lain for so long in the mind, casts a backward light over the road. And what was accomplished in fatigue, sometimes boredom, in the face of that absolutely solid presence that justifies it all, is transformed into a series of necessary and joyous moments. Walking makes time reversible."

On the turntable: "International Pop Underground"

On the nighttable: Frederic Gros, "A Philosophy of Walking"

Sunday, October 26, 2014

Sunday Papers: Nancy Snow

“Japan has too may politicians, but not enough politics.”

On the turntable: The Clash, "Give 'em Enough Rope"

Monday, October 20, 2014

Tyger, Tyger. Burning bright...

Of what do captive tigers dream,

Beneath the flawless blue of autumn skies?

Beneath the flawless blue of autumn skies?

On the turntable: Lovely Sparrows, "Daytrotter Session"

Sunday, October 19, 2014

Sunday Papers: Ivan Krylov

"An empty barrel echoes more loudly than a full one."

On the turntable: "Klubbjazz"

Friday, October 17, 2014

(untitled)

What erodes, creates.

Fuji admires her new look,

Thanks to recent rain.

Fuji admires her new look,

Thanks to recent rain.

On the turntable: Castenets, "Daytrotter Session"

Wednesday, October 15, 2014

(untitled)

Autumn rain so cold

That even the acorns

Pull on their wooly caps.

That even the acorns

Pull on their wooly caps.

On the turntable: Someone Still Loves You, "Daytrotter Session"

Tuesday, October 14, 2014

Sunday, October 12, 2014

Sunday Papers: St. Bernard

“What I know of the divine, I learned in the woods.”

On the turntable: "Putumayo Presents: Jamaica"

Monday, October 06, 2014

(untitled)

Like an old grey relative,

Standing as reminder for

The short memory of youth.

Standing as reminder for

The short memory of youth.

On the turntable: These United States, "Daytrotter Session"

Sunday, October 05, 2014

Sunday Papers: Frank Gibney

"Despite its many flaws, history will judge the Occupation a uniquely successful experiment in transplanted principles"

On the turntable: "The Rough Guide to World Music"

On the nighttable: "Foreign Correspondents in Japan"

Wednesday, September 17, 2014

(untitled)

The shadows of gaslamps

Lengthen the twilight

Of summer's final wane.

Lengthen the twilight

Of summer's final wane.

On the turntable: Annuals, "Daytrotter Session"

Sunday, September 14, 2014

Sunday Papers: Masa Iwatsuki

"Man destroys things focusing on efficiency.

Nature destroys things focusing on beauty.

Wind, rain, snow, sunlight; all are great sculptors."

On the turntable: Lee Morgan, "The Blue Note Years"

On the turntable: Lee Morgan, "The Blue Note Years"

Friday, September 12, 2014

Dust Never Sleeps

Ah, David Cozy

fished me in with a recently popular meme, asking me to list ten books that have stayed with me. Thinking completely off the top of my head, and in random order:

"The Razor's Edge," W. Somerset Maugham "The Quiet American," Graham Greene "The Sportswriter" (and its three sequels), Richard Ford "The Roads to Sata," Alan Booth "The Inland Sea," Donald Richie "Thank You and OK!," David Chadwick "The Forgotten Japanese," Miyamoto Tsuneichi "Japanese Pilgrimage," Oliver Statler "The Things they Carried, "Tim O'Brien "The Snow Leopard," Peter Matthiessen

and

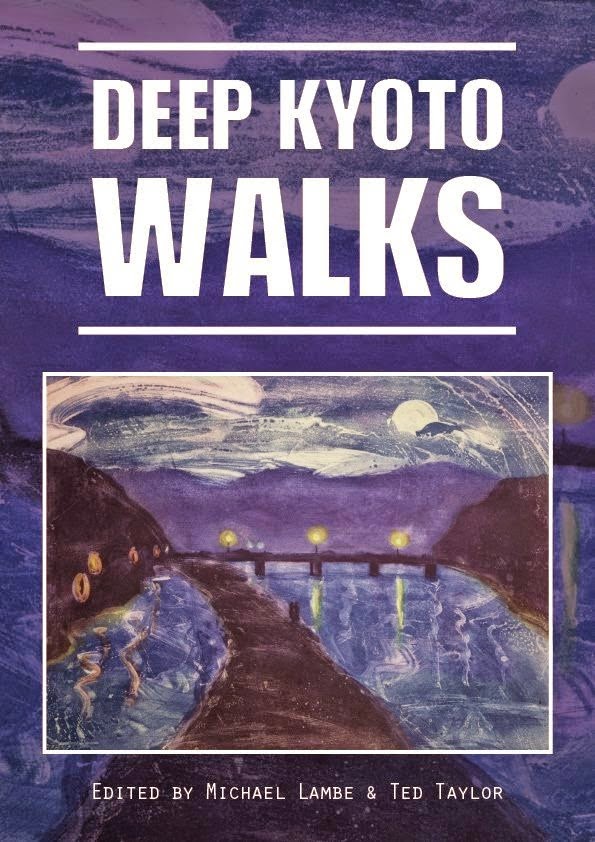

Deep Kyoto Walks

On the turntable: Bill Laswell, "Dreams of Freedom"

|

Tuesday, September 09, 2014

Fuji Sea to Summit, Day 3: Stone

I could barely open my eyes, which was a surprise since they'd rarely closed all night. I had slept in one of Japan's notoriously overcrowded mountain huts, forced to share a futon with a friendly man from Kyoto who had told me at dinner that he was a student of Sekishu-ryu, an old style of the tea ceremony usually reserved for the samurai. The futon was wedged between a small area enclosed by 2x4's, which were about 5 cm too short for me. I could extend my legs slightly into the next chamber, but as we were all sleeping head-to-foot, occasionally someone on the other side would give my feet a good kick. So I was forced to curl on my side in the fetal position, but within ten minutes the sembe-buton (thin as a rice cracker) would bring about an ache in the hips. I'd find relief by getting up and walking to the end of the corridor and looking down at the lights of Gotemba far far below. The rains had finally cleared.

And the early morning was gorgeous. The sun was coming through a thin veil of fog that had gotten itself hung up on the sharp edge of the volcanic cone. The sky went black to violet to blue in what felt like minutes, nothing between it and us at this altitude. Low vegetation glowed gold in the new light, brilliant against the deep black of the wet volcanic rock from which it stubbornly burst. There was a lot more vegetation here on the Fuji's southern slope, far more than I remembered from my previous clamber up the Yoshida trail on the opposite side.

Our party moved upward, ever so slowly. Nishikawa-san told us that he wanted to keep the pace slow so as to keep us from sweating in the cold of morning. From the 6th Station it normally takes 3 1/2 hours to the top, but our group took ninety minutes longer. As it was, I never once felt out of breath, never felt like I was laboring at all. The physical difficulties of the previous day had vanished with the rains. A few people mentioned symptoms of a mild altitude sickness, but as for me, I was simply out for a stroll, up Japan's highest mountain.

We were instructed to greet other hikers with a hearty, "Yo Mairi!" or "Happy pilgrimage". Most who were greeted this way seemed puzzled, and after they heard the words come from my mouth, they'd mistakenly repeat what they'd heard as "Good Morning!" Due to the early hour, most we encountered were returning from a night spent in one of the huts. All looked exhausted and had no doubt faced worse weather than we had. But the reward was in the views, stretching from the glittering glass of Yokohama and Tokyo to the north, and well past Shizuoka to the south. The entire length of the Izu peninsula was visible below, pointing its knobby finger out toward the land of my birth. Around the peninsula, the sea was a slightly different color, due to the extreme depth of Suruga Bay, one of the deepest in the world. At each hut we'd stop awhile to take in the view growing ever more panoramic. One of my companions joked that a climber usually looks for views of Fuji while hiking, but today, Fuji offered views of everything else.

We also made a few of the usual stops at some of the spiritually important sites on the mountain -- little clefts in the rocks stuffed with coins or other offerings, or the odd statue tucked into a fold in the lava. At the Ninth Station we stopped to offer kaji to the staff there, one a woman who looked almost Tibetan with her tanned face and long unkept hair. Beyond this, the horagai began to bellow, and Shunken-Sensei started us in a round of "Sange sange" which we kept up all the way to the summit. Looking up, I could see a number of heads looking down, wondering at this wave of sound rolling up toward them.

Fujinomiya Shrine was under major reconstruction, so we walked further around the crater for our goma ceremony. Before a small gathering of decapitated stone statues, the yamabushi sat in a row, while Shunken-Sensei led the chants as he did a variety of things with his hands, before tossing items into the fire burning before him. The chanting sounded almost Tibetan to me, and it was at that moment that I realized that I was sitting atop a landmass not only incredibly high, but one incredibly old. The atmosphere was timeless, a sense of being on the top of the world here. No vegetation, no life, but a feeling of place very very ancient. Just as the chanting finished a plane flew over, a bird of war, bringing with it a bit of irony since we'd just been chanting for world peace.

Nowhere to go but up. A handful of us pushed up the pile of ash that had built up to form the true summit. In the shadow of the abandoned weather station was a tall man-made stele that marked the peak. We walked past a group of young climbers flashing peace signs for photographs to climb up a crest of volcanic rock that stood a few meters higher. Above this was nothing more.

Nowhere to go but down. We descended via the Gotemba route, following in my own footsteps from 1995. This is one of the least used of Fuji's paths and it showed. Most of the huts we passed were mere ruins of weathered wood, though they had probably been in use on my previous descent. Tall piles of rocks had been piled before their front doors, a defiant means of preventing free accommodation. No real surprise here as the majority of the staff of mountain huts in Japan are blatantly mean-spirited. Shinier new huts composed of a stronger building material stood not far off in the dust. In front of one, a young woman clad in fleece threw wood and paper upon a fire in some sort of goma of her own.

Below the Seventh Station, the trail became a straight track of loose earth, of a steepness that pulled the body forward. Some of the older members of our group had an uncomfortable look on their faces, but the majority of us laughed as our footfalls increased in tempo and were soon in full cantor. I did a few small jumps as if I were skiing moguls, my feet sliding sideways across the ashen powder.

Our trail continued past the pimple on Fuji's eastern flank: Hōei-zan, a volcanic vent that had blown open in the mountain's most recent eruption in 1707. My nose was running slightly from all the ash being kicked up, and as the clouds closed in on us, the world became dim and grey.

Then, just above us at a junction came the fuzzy outline of a yamabushi, dully silhouetted against the mist, hands clasped in prayer before her. It was the calm woman who had showed up yesterday, yet had opted out of the ascent itself. I felt relieved, knowing that just beyond her was the ephemeral world of buses and beers and baths. But the sight of this figure standing on the edge of the slope was a vision of timelessness, of mountains waltzing across the eons, and the sense of awe that continues to pull us into the dance.

On the turntable: Freddie Hubbard, "The Blue Note Years"

On the nighttable: Jordan Sand, "Tokyo Vernacular"

Saturday, September 06, 2014

Fuji Sea to Summit, Day 2: Soil

Nishikawa-san looked exhausted. He had only gotten four hours of sleep over the last two nights, busy in wearing two hats, that of the organizer and guide of this event, and as a local yamabushi. The true leader today was supposed to have been Hatakehori-sensei, whose study of this Murayama Kōdō and subsequent book had led to this event being organized three years before. While Sensei was ostensibly the leader of this Fuji Mine Iri Shūgyō climb, his back had been acting up so he had been forced to bow out. This left poor Nishikawa-san to do the heavy lifting.

But he knew the route well, having worked quite hard to restore signage and explanatory signs in order to resuscitate this, the oldest of Fuji's hiking paths, with roots going back to the Heian period. And his efforts seemed to be paying off. With Hatakehori as the brains, and Nishikawa as the muscle, Shogo-in's Shunken-Sensei was the heart. A surprisingly young man for such a high position, he felt that it was important to restore the yamabushi to their rightful relationship with the mountain, as the yamabushi were the only ones who had climbed the peak in the old days. Fuji's recent addition to the World Heritage list had been awarded for the mountain's cultural importance, and it was the yamabushi who had crafted that culture in the first place. This particular event appeared to be effective PR, as the crowds who came out to be blessed increased year to year.

Unlike Nishikawa-san, I had slept quite well, a surprise since I was sharing a large open room with close to twenty snoring men. Upon arrival the previous evening, I smiled when I found myself back at Jumbo, in whose courtyard I had taken a brief catnap last November. When the lights came on at 4 a.m., I snuck down to a lukewarm bath for a quick dip, then grabbed a restorative coffee from the machine out front. This would have to keep me until breakfast four hours further on.

Our numbers were half what they had been the day before, as most had taken the one-day option. Headlamps attached, we remaining twenty immediately entered the forest, leaving behind the camera toting passersby who the previous day had been quick to snap a photo of our procession with their phones, a device that serves as physical manifestation of the old proverb "ichigo ichie." These days, not a single moment of life is beyond capture.

Due to the early hour the great horagai conches were silent, and the only sounds to be heard was the crackling of the tall electrical towers at the edge of the village. As the land sloped upward, we moved into the gullies carved out by a thousand years of human feet. As this trail had been somewhat dormant over the last century, the more recent carving had been undertaken by water, eventually making for a rougher, more difficult passage. To avoid this, a newer trail had been tramped into the berm above, and as we walked it I looked down into the black earth of the gully, hearing the voice of Sting in my head repeating again and again that we "work the black seam together."

This new trail was well kept, and Nishikawa-san continually stopped to point out sections of more recent work that he had been personally involved in, most of these for the prevention of erosion. The Japanese are fantastic at building trails, but not always so good at their upkeep, the result being that they are left alone to erode and wash away. Nishikawa also spent a good deal of time pointing at certain rocks and strata. Any discussion of Fuji inevitably involves geology.

There was an obvious absence of fauna, but the flora was magnificent: great swatches of ferns erupting upward as one; the bright green of moss softening the tone of the black, hard, volcanic rock. In a demonstration of the irony of nature, the most fertile stretches of moss were found just above the Nyonindō women's hall, which had once served as the upper limits that that gender could proceed. All that was left here now was a small clearing where the hall had once stood, the trees before it purposefully kept low so as to offer a view of the sacred peak.

Somewhere around lunchtime, the rains began, which didn't cease until the following morning. This dense forest offered some respite, but after an hour or so my energy began to wane. We were attempting a 2000 meter elevation gain, which Hatakehori-san had claimed is the most possible in any single day climb anywhere in Japan. (Though I silently and respectfully disagreed, as I had ascended over 2300 meters when I had hiked Fuji back in 1995.) But more than the climb, it was the conditions that were taxing. When given the option, nine of our group had opted to quit early and walk up a perpendicular road to a bus stop. One of these was a yamabushi would had been suffering terrible blisters due to attempting the ascent in waraji sandals bound in plastic string rather than the traditional straw. How foolish, I thought, not to look after yourself and allow a macho sense of pride to overshadow self-preservation. As someone who guides in the mountains, I am quite unforgiving of this type of folly, which puts not only oneself but others at risk.

The rest of us carried on. One man came around and offered us sweets, an act that is almost a Japanese cultural trait by now: When the going gets tough, the candy comes out. Perhaps the sugar had fueled a certain giddiness amongst the yamabushi, who would happily clamored up ropes, or run up the steeper embankments. If one of them performed an act in a particularly cool and dexterous manner, he'd be told by the others that he "looks like En," refering to En-no-Gyoja, founder of the Shugendō sect in the 7th Century.

The rest of us weren't feeling so spry. To spur us on, Shunken-sensei started up the call-and-response chant familiar to all sects of Shungendō. His voice was powerful, touched with a resonance that hinted at a beautiful singing voice. But his melodic calls of "Sange sange!" began eventually to sound like "Sunday, Sunday," and coupled with the rain became to me "Gloomy Sunday," and we all know what that leads to. My mood bottomed out during one steep section of trail that had been partially blocked by dozens of fallen trees, which required a lot of physically-taxing over and under, my backpack often snagging these trunks to bring down a sudden cascade of rain. As I looked at the Montbell pack of the guy in front of me, with its brand name of "Zero Point," I thought, "Yep, there is no real point in this, is there?"

But the wet fecund forest itself offered resurrection, as did the broad meadow filled with wildflowers. Here and there too were little Jizo statues poking their heads out from the undergrowth to spur us on. At the height of the early Meiji period anti-Buddhist backlash, all of the little figures on the mountain had been decapitated. Nishikawa-san told us that written records gave the numbers of statues that had once been along the trail, and he personally had spent many an afternoon poking through the brush, trying to find their little bodies. Many still remain missing. He also told us a humorous anecdote about how one- and ten-yen offerings tend to stay in front of the statues, but that one-hundred yen coins are usually carried off.

After twelve full hours, we finally arrived at the 6th Station Hōei mountain hut, our digs for the night. Wet layers thus removed, the beer began to flow, and soon a party-like atmosphere overtook the hut. A couple of new yamabushi turned up, including one middle-aged woman who carried a demeanor of calm solidity. The monks all drank and dined together, but one of them came over to our small table of four, and talked a great deal about the sect. It was a pleasant night, and despite the 10 km and 2000 meters of constant up, my legs felt fine enough to sit cross-legged at the table. But bedtime came quite soon...

On the turntable: "The Rough Guide to Nigeria and Ghana"

Friday, September 05, 2014

Fuji Sea to Summit, Day 1: Asphalt

Left leg bent at the knee, I leaned out over the abyss. Beneath, all was calm and cold, but should the dry rocks begin to heat up and liquify, more was at stake than my mere toppling forward and down. It would mean the evacuation of the 750,000 people who live and work at the foot of this colossal mountain.

The road here began two days before. I had met an assembled group of 40 souls at Fuji City's Kinomoto Shrine, who would follow nine yamabushi up to the summit from the shores of nearby Suruga Bay. The leader led us to those waters on horseback, beneath the shade of pines bent from decades of winters, then up and over a concrete embankment and onto the stone-laden beach of Tago-no-ura. Here the yamabushi stripped down to their fundoshi and immersed themselves to their waists, hands clasped before them in prayer. I was playfully invited to join them, but merely rolled my pant-legs as high as they would go and walked into the sea. The water wasn't very cold, but as each wave struck my legs it would splash upward, until I found myself quite wet anyway. The chanting finished, the yamabushi lowered themselves up to their necks in the water, as a passing fishing boat rolled its wake toward them. Peering up from over the strand of pines behind, the great mountain made no comment.

Before leaving the beach, I picked up a smooth stone and put it into my pack, intending to place it atop Fuji's peak. We moved along the concrete embankment, sections of which were being shored up in order to protect the homes here from future tsunamis. We weaved between these homes, arriving eventually at a Fujizuka that mimicked the mountain rising directly behind this man-made summit.

The yamabushi chanted to both, before turning to bless the locals standing nearby. Known as kaji, these rituals involved the head yamabushi stepping over children who were sprawled atop a tarp covering the ground. (Ironic how they were not allowed to lie directly atop the dirt beneath, considering that the entire belief system of the yamabushi and the Shugendō sect is about finding mindfulness and enlightenment within nature.) The kids looked at the yamabushi with a mixture of fascination and horror, and I could imagine that in the old days, parents had threatened naughty children with being snatched by these mountain monks if they misbehaved. The adults lined up next, and to the collective accompanying chants, the head priest rubbed his staff twice down their backs before laying it along the length of the spine and giving it a gentle push.

As we made our way through the city, the kaji was repeated at least a half dozen more times, occasionally at shrines, but more often along one of the city's main streets. Traditionally, the yamabushi have come from the ranks of the ordinary folk in Japan, and in these rituals, this connection was still apparent. As the monks went through their routine, the rest of us chanted the Heart Sutra along with them, or received tea and snacks as settai. As I was the only foreign participant, I received only slightly less attention than the sight of a yamabushi proudly riding through town on horseback. At every stop, someone would come over to get my story.

If I had been honest, I would have mentioned sore feet and a restless mind. When I do my own 'road work' I will rely on the iPod to get me through all the monotonous industry and traffic pushing in too closely. Today, I heard only the rhythm of feet, the jingling of bells. The pace of the group was much slower than what I would have done, and my knees ached from a stride half of what it should be, which meant of course that I took twice the number of steps. Alone, I probably would have covered the 20km by 1 pm. As a group, we finished after 6.

We spent the better part of the morning weaving our way through Fuji City. If you've ever taken the Shinkansen from Tokyo to Kyoto, you know Fuji City. It's the place that ruins any decent photographs of the mountain itself, a place filled with ugly apartment blocks and tall smokestacks striped red and white. At some point we crossed the Tokaidō again, turning right and directing ourselves straight toward the mountain, a trajectory that we'd hold for the next two days. Along the way, we made a short stop at a lesser Sengen shrine on the edge of town (Sengen shrines being dedicated to the Goddess of Fuji). Here I stood in the heat of midday, listening to the prayers harmonize with the voices of late season cicada, chanted by a very old priest with a very limber back.

As the day wore on, we moved beyond the suburbs and into a series of smaller villages surrounded by wide tea plantations, walking single file, our party being a few legs shy of being a centipede. Our last prayer stop for the day was at Jirocho-cho, named for the famous late Edo period yakuza Shimizu no Jirocho, who had been active in this area. The subject of over 100 films, this Japanese Robin Hood eventually went on to become a police officer for the new Meiji government, and allegedly served as a bodyguard for the equally legendary Yamaoka Tesshū.

Full up on watermelon and boiled peanuts, we climbed through patches of forest that served as the borders of rice fields. At the corner of one field, was a small shrine that looked like a thatch cabin, above which hung tall poles of bamboo, the lair of the water god, greatly honored in this landscape of steep lava-carved slopes which pose tricky challenges to irrigation.

And finally then to Maruyama Sengen Jinja, as both the sun and the rain began to fall. I had visited this shrine during my circumambulation of Fuji last autumn, and had been awed by its proud trees and beautiful old statues. There were a handful in a lesser hall that I hadn't seen, exposed now to hear the final chants of the day...

On the turntable: "Only 2 Degrees of Separation"

On the nighttable: Stephen Mansfield, "Tokyo: A Cultural and Literary History"

Monday, September 01, 2014

(untitled)

Water tumbling downward

Rocks flowing up;

We walk the spaces between.

Rocks flowing up;

We walk the spaces between.

On the turntable: Richard Swift, "Daytrotter Session"

Sunday, August 31, 2014

Sunday Papers: Brad Warner

"The New York Times and Huffington Post represent so-called 'responsible journalism.' That means that they are practiced in the art of writing lurid allegations in such a way as to seem tasteful while still pushing all the same emotional hot buttons that writers for the New York Post or the Sun push far less pretentiously."

On the turntable: "Cafe Del Mar, The 20th Anniversary"

Sunday, August 24, 2014

Sunday Papers: B.K.S. Iyengar

“Nothing can be forced, receptivity is everything.”

On the turntable: "Putumayo Presents French Cafe"

Saturday, August 23, 2014

The Low Road to Nara

Standing before the concrete water basin, I am suddenly enshrouded in white. As I was undergoing my water purification before entering Kashihara Jingu, a group of about two dozen priests surround me, and begin to go through their own ablutions. Slightly intimidated, I move away from them, over the raked gravel that covers this wide open space. In shrines of this scale, the sense of airiness always feels that the whole place will take flight. Perhaps the stone covering the grounds is a way to tether it to the earth.

In entering the shrine, I have left the Shimotsumichi, one of the three old roads that had once led to the Heijō palace from the south. This palace was the home of the Imperial court during the Nara period, which lasted for the majority of the 8th Century, a time when that city was considered the true end of the Silk Road, its treasures having been filtered through the parallel palaces of the T'ang.

I allow my detour to continue, swinging widely to the east, in order to visit the site of the old Fujiwara palace that preceded Heijō as the capital, though for a mere 16 years. This site served as both a physical and temporal transition from the earlier Asuka capital a short walk south. I love this area, so rich in history, so fertile and broad in the never-ending rice paddies and the tell-tale tufts of forest that mark the eternal resting places of Imperials dead for over a millennium. This Fujiwara-kyō is simply massive, taking me a good half and hour to cross, passing dozens of two-meter high pillars laid out in parallel rows here and there across the plain. Marking the locations of ancient buildings, I lean on what I expect to be wood, but find to be instead some spongy synthetic material. The color is similar to my T-shirt, which had been orange when I put it on at dawn, but is by now sweat-soaked to a dull ochre.

Heading west brings me to Ofusa Kannon-ji temple, its courtyard filled with roses. Above, hundreds of glass wind chimes have been hung. In summer, the Japanese believe that a wind chime helps to cool the body, since the sound of striker on glass is the sound of the movement of wind. As I pass beneath however, the breeze stirs up not a delicate jingle but a cacophony of a fully-loaded tray dropped in a restaurant.

Back to the old road proper, narrow and lined with old wooden structures. A pair of old men hang paper lanterns over the road, the sign of an impending festival. I'm on the outskirts of Yamato Yagi, a town famed for its preserved look. Unlike the broader streets of the later Edo period post-town, these older lanes are far narrower, the structures darker and less earthen. At the crossroads of the equally old Yokōji road, a man beckons me into what had once been an old inn and is now a very simple history museum. The caretaker is knowledgeable and enthusiastic, but all too often his enthusiasm turns to me and just how remarkably foreign I am. I have complained about this in the past, where I want to have an intelligent conversation about history and culture, yet the other party can't see past my eye-color and the unique structure of my nose. I can understand the natural curiosity about 'other,' I mean, at this very moment I am seeking out that which is particularly Japanese. But after a few basic polite questions, it is nice to move on.

So I do. Beyond the train station, the town becomes yet another suburb, and beyond this I follow a small river. I love Nara for its water. Steams cross and recross, leading to and from what must be hundreds of small lakes and ponds that dot this entire basin. I am accompanied by water the rest of the day. The river here is alive and healthy, filled with fish and turtles and cormorants. The lower tree branches on the far bank are bedecked with trash and debris, compliments of a pair of powerful storms that roared through the Kansai during the past two weeks. The pillars of bridges are similarly tangled with a snarl of reeds and tree limbs.

And so it goes for the next six hours. Where the earlier part of the day had been a delightful stroll along the cusp of history, the rest of it is spent atop a berm, with water ever to my right, houses representing a half-dozen different generations to my left. On such a hot day, the water should be inviting, but factory after factory shadow the canals on the far bank. I get a short reprieve in the form of a small village completely surrounded by moats like a medieval European town, but here too the water is a suspicious hue.

At this point, I am puzzled as to why the maker of the map I am following chooses to send me to the west, rather than on the due-north trajectory that would take me directly to the main gate of Heijō palace. Later at home, as I look at Google Street View to see what I missed, I notice that he did me a favor in detouring me off a narrow, busy road with no apparent shoulder. Instead, I walk the bank of a much wider river, all the way into Nara proper. Along the way, I find a mystery. Six stone Jizo statues are lined up nearly behind a tree, but behind them is what looks like a cemetery, though devoid of all grave markers. Even odder is that each grave looks freshly dug, these symmetrical little piles of earth topped with a pair of tubes meant to hold flowers. I wonder if the people at rest here have been recently moved, their old plots now earmarked for some construction project. As we have just passed the Obon holiday, I further wonder if the souls of these people had been able to find the way to their new home.

Further on still, I come to a small park that supposedly contains a marker for the palace's old gate. The park is overgrown and unkept, and amidst the high grass I see only a few stones written with poetry. Yet upon one has been carved the illegible, flowing grass-style Chinese characters that may be commemorating the old gate. Sharing the name with its better known descendant in Kyoto, the Rashomon here is as equally absent as the newer one about which the film was made. And where Kyoto's grand old Suzuku boulevard now goes by the name of Senbon-dōri, here, what had once been the palace's main thoroughfare is now a canal that carries away what the modern city of Nara now longer needs, serving as an ironic metaphor to Japan's relationship with its own history.

On the turntable: "Rhythmes et Melodies de L'Inde Classique"

On the nighttable: Donna Henes, "The Moon Watcher's Companion"

Tuesday, August 19, 2014

Upon us All a Little Rain must Fall (Ise Betsu Kaidō)

The land on either side of the train was covered in a fine green quilt. Along the stitched edges, a casually dressed pair walked beneath umbrellas blooming upward against the rainy sky.

Damn you Mie and your damned changeable weather! The forecast just an hour before had been for rain early, then cloudy skies. But now it showed rain all day. The view from my train seat served as co-conspirator.

Back in Tsu lot much later, I returned to the stone that I’d passed three days before, which demarcated the southern terminus of the Ise Betsu Kaidō, another spur branch that connected with the Tōkaidō 8 km to the northwest for the convenience of Kyoto pilgrims heading to the Grand Shrines of Ise Jingu.

The rain had dulled to a fine mist, so I didn’t bother to unfurl my umbrella, lashing it instead to the side of my daypack. I ziz-zagged my way out of Tsu, through quiet rural neighbourhoods. It wasn’t long before I arrived at the massive Takata Honzan, headquarters for the eponymous brand of Pure Land Buddhism. The temple had a long history, though the modern halls didn't reflect that. Their grandeur was instead represented by its size, a hint that financially this temple was doing very well indeed. Workmen rushed about, changing banners for the throngs expected during the Obon holidays. With little of interest barring the spectacle of scale, I quickly left the gates and was back walking again.

The rest of the day was spent along this small road, which wasn’t particularly interesting but at least it kept me in the countryside. The humidity was incredibly high. I don’t think I’d ever walked in such intense humidity . The day threatened rain, and when it eventually fell, I felt relief, as the humidity index dropped quite a few percentage points along with it. Then relief turned to frustration as the skies threw at me everything they had.

After lunch I left the rather bland farming roads for the larger, more heavily trafficked roads, with the pachinko and the convenience stores and the cake shops. So many cake shops. From that point on, I began to notice the signs for dentists.

The rain eventually let up, and some blue sky began to reacquaint itself with the earth below. This new lighting revealed a more attractive landscape, of woodland and fields, and quainter villages of a older look. When I first came to Japan, I loved this old style of architecture, and would go out of my way to find places like this. Today, my eye is more drawn to the anomaly of Western buildings of which one or two can often be found, though those too have have one foot in the 19th Century.

Then finally I ran into the Tōkaidō at the post town of Seki, passing beneath the great torii arch that faces the direction of Ise Jingu. The beautiful preserved look of the town was as good as it gets anymore. After all, this was the Tōkaidō, the granddaddy of the old feudal highways, and I promised myself I would follow its length before long. But it also made me ask myself just how far I want to take this walking of old roads. As this day had proven, there are small spur roads simply everywhere in this country. How minor a road do I want to walk? That said, each of those roads does have its own history, but how much of that history is still visible and remembered?

MAP: http://latlonglab.yahoo.co.jp/route/watch?id=946677c21ff84f969a3cf159a271c5ec

On the turntable: Skatalites, "Skabadabadoo"

On the nighttable: Christal Whelan, "Kansai Cool"

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)